Coastal defence of Vancouver in both world wars

Coastal defence of Vancouver in both world wars: Preparing for attacks that never came

Article / November 7, 2015 / Project number: 15-0150

Vancouver, British Columbia — Does “Old Fort UBC” sound a little far-fetched? It’s not. In 1914, part of the University of British Columbia’s (UBC’s) Point Grey campus was officially designated a “fortress area.”

The history of the fortifications on Point Grey began in the summer of 1914. When war was declared against Germany in July, Vancouver had no permanent defences. Naval forces based at Esquimalt, on Vancouver Island, consisted of Her Majesty's Canadian Ship (HMCS) Rainbow, which is an Apollo-class protected cruiser, an obsolete light cruiser used for training; and two British sloops-of-war, then in Mexican waters. Between these two and their home port lay the Seiner Majestät Schiff (SMS – German for His Majesty's Ship) Leipzig, a German cruiser.

When HMCS Rainbow left with a crew of volunteers to rescue the sloops, British Columbians were thrown into a panic. Another German warship, SMS Nürnberg, was reported to be steaming toward the coast, and there were four other raiders on the loose in the Pacific. There was nothing to prevent them from attacking the seaports of B.C.

The Canadian Army sends guns from Ontario by rail

HMCS Rainbow and the British Navy sloops, Her Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Algerine, a Phoenix-class sloop; and HMSShearwater, a Condor-class sloop, returned safely in mid-August. HMS Shearwater at once unloaded two naval guns for positioning in historic Stanley Park, which was named for Lord Frederick Stanley, Governor General of Canada in 1888. Two five-inch guns from the Cobourg Heavy Battery Canadian Garrison Artillery arrived by rail from Ontario. This Battery later became part of present-day 33rd Medium Artillery Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery.

According to one eyewitness, “drawn by trucks, the gun carriages rumbled through downtown streets and out to Point Grey, where positions had been prepared about half a mile east of the present washout gully.” As the guns were rolled into position, one was found to have a cracked breech-block; sabotage was suspected but never proven.

The German scare subsided that autumn with the arrival of more friendly warships at Esquimalt. One of these, ironically, was the Izumo, a Japanese armoured cruiser supplied under the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of 1902. With this reassurance, the Point Grey guns were withdrawn. The Stanley Park fortifications were reinforced, but with the return of peace in 1918, Vancouver reverted to its peacetime footing.

The improvised batteries of 1914 were the precedent for a 1937 plan to make the city a “defended port.” A counter-bombardment battery of three six-inch-calibre guns was proposed for Point Grey. Its function would be to engage vessels approaching Burrard Inlet. A similar close-defence battery was planned for Ferguson Point in Stanley Park and work began there in February 1938.

Militia labours day and night to build defences in 1939

It was not until late August 1939, however, when war against Nazi Germany seemed inevitable, that action was taken at Point Grey. The militia was mobilized on a weekend and men laboured on the headland at night under floodlights and all day, despite rain. Quick-drying cement was rushed in from Seattle for two temporary gun platforms near the cliff to support six-inch coastal guns obtained from Esquimalt.

Behind the gun platforms, workers built permanent installations of reinforced concrete. There were three circular gun emplacements with underground magazines and connecting tunnels, and an elevated command post overlooking the entire battery. The site was a part of the campus formerly enclosed by Marine Drive as it skirted the point. The road was straightened to the present route of Marine Drive to bypass the headland, now a restricted military reserve.

The wartime defences of Vancouver were more extensive than the two batteries planned in 1937. A fort at the First Narrows guarded the passage into the harbour, and an examination gun was located at Point Atkinson. Steveston, south of Vancouver on the Fraser River, had its own battery of 18-pounder guns until 1943. The posts were linked by a communications network, and from 1942 onward, they were coordinated by a fire command post at West Bay, on the north shore. In the same year, installation of the battery searchlights was completed. The towers for two of these lights remain below the point on present-day Towers Beach.

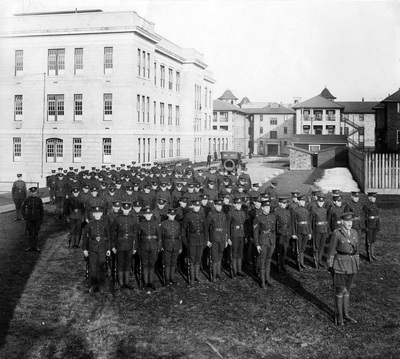

The militiamen who served the coastal guns of the lower mainland were from the 15th Coast (formerly Field) Brigade, Royal Canadian Artillery. Its 58th Heavy Battery took charge of the Point Grey fort.

The coastal attack that never came

The bane of the coastal gunners was the long watch for the attack that never came. Point Grey was equipped with a six-pounder gun that fired across the bows of such ships. In September 1942, the gunners fired ahead of a delinquent fishing boat. The shell ricocheted off the water and hit a freighter, which settled in the water below Lions Gate Bridge.

Vancouver’s guns were really a last line of defence. The waters off British Columbia were patrolled by the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Canadian Air Force. Any warship intent on reaching Vancouver would have to pass the heavy batteries of Victoria-Esquimalt or, if coming from the north, evade the guns of Yorke Island in Johnstone Strait. As Vancouverites rightly suspected, a Japanese naval bombardment was unlikely. A carrier-borne air attack was more probable, but the city’s anti-aircraft defences were inadequate. The community`s nervousness just after Pearl Harbour was understandable. Vancouver received its quota of anti-aircraft guns in early 1942; a few months later Japan’s navy lost its offensive capacity.

Intricate mechanisms and long concrete tunnels

Writing in 1940, a British journalist described “The big guns that guard British Columbia’s vital harbours.” The description could have applied to the fort at Point Grey:

“Mounted on huge concrete emplacements stand the guns, terrific chunks of metal and tiny pieces of intricate mechanism, all balanced so finely that the whole can be turned and twisted by means of a wheel worked between the fingers of one hand. Underneath are miniature Maginot Lines: long concrete subterranean tunnels extending hundreds of yards between observation posts and the guns, and through which ammunition can be brought without exposure to enemy fire. Far beneath the guns are magazines, holding supplies of explosives and shells.”

The Point Grey battery was, like France’s Maginot Line, not invincible. Because the guns could only be elevated 15 degrees, their range was limited to eight miles. Gun No. 3, in the southernmost emplacement, had a bore so worn and pitted that it was never to be fired “except in action.” A test firing was successfully made, at some risk, in 1942.

Fort Camp, the battery’s barracks, was acquired by UBC in 1946. Dr. Gordon Shrum, retired dean of graduate studies and commander of the university's Canadian Officers Training Corps from 1937 to 1946, recalled that it consisted at the time of six long huts, a mess-hall, and a few smaller buildings. On his initiative, more huts from the Tofino air base were brought by barge. Building materials were in short supply and the additional huts were reconstructed with nails that had been straightened by the students. Heating pipes only came after Christmas. Despite its deficiencies, the camp filled an urgent need for accommodation for a student body that had trebled.Fort Camp is no more; its last remains were cleared away to make room for UBC’s Museum of Anthropology. The museum straddles the battery, whose centre section has been partly incorporated in the museum plans. One gun emplacement stands apart, intact, and partially-restored at the north end of the site. Nonetheless, the now-crumbling ruins of our coastal defences seem a rather sad and incongruous part of our history; a part that evokes memories of the wartime fears of British Columbians, of the citizen-soldiers who manned the post, and of that time when UBC was at war.

By Major (Retired) Peter Moogk, PhD, retired Professor Emeritus of history at UBC and Curator of the Museum and Archives of the 15th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

Article / November 7, 2015 / Project number: 15-0150

Vancouver, British Columbia — Does “Old Fort UBC” sound a little far-fetched? It’s not. In 1914, part of the University of British Columbia’s (UBC’s) Point Grey campus was officially designated a “fortress area.”

The history of the fortifications on Point Grey began in the summer of 1914. When war was declared against Germany in July, Vancouver had no permanent defences. Naval forces based at Esquimalt, on Vancouver Island, consisted of Her Majesty's Canadian Ship (HMCS) Rainbow, which is an Apollo-class protected cruiser, an obsolete light cruiser used for training; and two British sloops-of-war, then in Mexican waters. Between these two and their home port lay the Seiner Majestät Schiff (SMS – German for His Majesty's Ship) Leipzig, a German cruiser.

When HMCS Rainbow left with a crew of volunteers to rescue the sloops, British Columbians were thrown into a panic. Another German warship, SMS Nürnberg, was reported to be steaming toward the coast, and there were four other raiders on the loose in the Pacific. There was nothing to prevent them from attacking the seaports of B.C.

The Canadian Army sends guns from Ontario by rail

HMCS Rainbow and the British Navy sloops, Her Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Algerine, a Phoenix-class sloop; and HMSShearwater, a Condor-class sloop, returned safely in mid-August. HMS Shearwater at once unloaded two naval guns for positioning in historic Stanley Park, which was named for Lord Frederick Stanley, Governor General of Canada in 1888. Two five-inch guns from the Cobourg Heavy Battery Canadian Garrison Artillery arrived by rail from Ontario. This Battery later became part of present-day 33rd Medium Artillery Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery.

According to one eyewitness, “drawn by trucks, the gun carriages rumbled through downtown streets and out to Point Grey, where positions had been prepared about half a mile east of the present washout gully.” As the guns were rolled into position, one was found to have a cracked breech-block; sabotage was suspected but never proven.

The German scare subsided that autumn with the arrival of more friendly warships at Esquimalt. One of these, ironically, was the Izumo, a Japanese armoured cruiser supplied under the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of 1902. With this reassurance, the Point Grey guns were withdrawn. The Stanley Park fortifications were reinforced, but with the return of peace in 1918, Vancouver reverted to its peacetime footing.

The improvised batteries of 1914 were the precedent for a 1937 plan to make the city a “defended port.” A counter-bombardment battery of three six-inch-calibre guns was proposed for Point Grey. Its function would be to engage vessels approaching Burrard Inlet. A similar close-defence battery was planned for Ferguson Point in Stanley Park and work began there in February 1938.

Militia labours day and night to build defences in 1939

It was not until late August 1939, however, when war against Nazi Germany seemed inevitable, that action was taken at Point Grey. The militia was mobilized on a weekend and men laboured on the headland at night under floodlights and all day, despite rain. Quick-drying cement was rushed in from Seattle for two temporary gun platforms near the cliff to support six-inch coastal guns obtained from Esquimalt.

Behind the gun platforms, workers built permanent installations of reinforced concrete. There were three circular gun emplacements with underground magazines and connecting tunnels, and an elevated command post overlooking the entire battery. The site was a part of the campus formerly enclosed by Marine Drive as it skirted the point. The road was straightened to the present route of Marine Drive to bypass the headland, now a restricted military reserve.

The wartime defences of Vancouver were more extensive than the two batteries planned in 1937. A fort at the First Narrows guarded the passage into the harbour, and an examination gun was located at Point Atkinson. Steveston, south of Vancouver on the Fraser River, had its own battery of 18-pounder guns until 1943. The posts were linked by a communications network, and from 1942 onward, they were coordinated by a fire command post at West Bay, on the north shore. In the same year, installation of the battery searchlights was completed. The towers for two of these lights remain below the point on present-day Towers Beach.

The militiamen who served the coastal guns of the lower mainland were from the 15th Coast (formerly Field) Brigade, Royal Canadian Artillery. Its 58th Heavy Battery took charge of the Point Grey fort.

The coastal attack that never came

The bane of the coastal gunners was the long watch for the attack that never came. Point Grey was equipped with a six-pounder gun that fired across the bows of such ships. In September 1942, the gunners fired ahead of a delinquent fishing boat. The shell ricocheted off the water and hit a freighter, which settled in the water below Lions Gate Bridge.

Vancouver’s guns were really a last line of defence. The waters off British Columbia were patrolled by the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Canadian Air Force. Any warship intent on reaching Vancouver would have to pass the heavy batteries of Victoria-Esquimalt or, if coming from the north, evade the guns of Yorke Island in Johnstone Strait. As Vancouverites rightly suspected, a Japanese naval bombardment was unlikely. A carrier-borne air attack was more probable, but the city’s anti-aircraft defences were inadequate. The community`s nervousness just after Pearl Harbour was understandable. Vancouver received its quota of anti-aircraft guns in early 1942; a few months later Japan’s navy lost its offensive capacity.

Intricate mechanisms and long concrete tunnels

Writing in 1940, a British journalist described “The big guns that guard British Columbia’s vital harbours.” The description could have applied to the fort at Point Grey:

“Mounted on huge concrete emplacements stand the guns, terrific chunks of metal and tiny pieces of intricate mechanism, all balanced so finely that the whole can be turned and twisted by means of a wheel worked between the fingers of one hand. Underneath are miniature Maginot Lines: long concrete subterranean tunnels extending hundreds of yards between observation posts and the guns, and through which ammunition can be brought without exposure to enemy fire. Far beneath the guns are magazines, holding supplies of explosives and shells.”

The Point Grey battery was, like France’s Maginot Line, not invincible. Because the guns could only be elevated 15 degrees, their range was limited to eight miles. Gun No. 3, in the southernmost emplacement, had a bore so worn and pitted that it was never to be fired “except in action.” A test firing was successfully made, at some risk, in 1942.

Fort Camp, the battery’s barracks, was acquired by UBC in 1946. Dr. Gordon Shrum, retired dean of graduate studies and commander of the university's Canadian Officers Training Corps from 1937 to 1946, recalled that it consisted at the time of six long huts, a mess-hall, and a few smaller buildings. On his initiative, more huts from the Tofino air base were brought by barge. Building materials were in short supply and the additional huts were reconstructed with nails that had been straightened by the students. Heating pipes only came after Christmas. Despite its deficiencies, the camp filled an urgent need for accommodation for a student body that had trebled.Fort Camp is no more; its last remains were cleared away to make room for UBC’s Museum of Anthropology. The museum straddles the battery, whose centre section has been partly incorporated in the museum plans. One gun emplacement stands apart, intact, and partially-restored at the north end of the site. Nonetheless, the now-crumbling ruins of our coastal defences seem a rather sad and incongruous part of our history; a part that evokes memories of the wartime fears of British Columbians, of the citizen-soldiers who manned the post, and of that time when UBC was at war.

By Major (Retired) Peter Moogk, PhD, retired Professor Emeritus of history at UBC and Curator of the Museum and Archives of the 15th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery