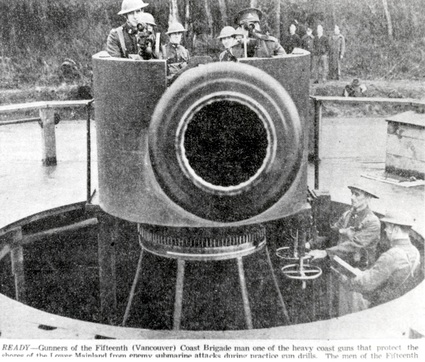

Gunners Want to See Action

"Gunners Want to See Action" read the caption for this 1940 press photo that looks down the muzzle of a 6-inch gun at Point Grey. The men in the pit are operating the traversing mechanism on the pivot mounting

Vancouver Defended, Peter N Moogk, pg 73

Early in 1940 the Vancouver newspapers ran a series of morale-boosting articles on the airmen and soldiers guarding British Columbia. One month before the fall of France a correspondent was unfortunate enough to describe the Victoria-Esquimalt gun batteries as "miniature Maginot Lines." On February the 14th Peter Stursberg of the Vancouver Daily Province was allowed to observe a firing practice from the flank observation post at Point Grey. Though the Province spoke of "heavy guns...somewhere in Vancouver" being "groomed for business," the facts were more prosaic. Major C.K. Rosebrugh, second-in-command of the 15th Coast Brigade, reported to area headquarters "14th February, A.M. One-inch aiming rifle practice at Point Grey. Visibility was quite poor, especially the left half of the zone where the maximum was about 4,000 yards. A total of 75 rounds of one-inch aiming was (sic) fired in five series at ranges between 2,100 and 2,300 yards. The target consisted of two floats representing a destroyer towed by a launch in the Gulf of Georgia off Point Grey and this practice was, for most of the men. the first time that they had fired the guns to seaward. In addition to the aiming rifles, there were sub-calibre tubes for a 3-pound shell that could also be inserted into the main bore. The tubes permitted live-firing drill at little cost and without wear to the gun's barrel. A 3-pounder shoot occurred on the following day when no reporters were present. For all practice firings maritime traffic was forewarned by the press to stay clear of the target zone and, as an additional warning, a red flag was flown from the battery flagstaff that customarily carried the Union Jack. It was hard to get excited about the firing of a one-inch aiming rifle and Peter Stursberg did his best to dramatize the event.

As the order rang out, the men in the O-Pip (observation post) became tense, Before that we had been chatting and glancing idly out at the two dots moving slowly across the grey sea.

A bombardier, his eye glued to the range finder, had kept on repeating "on sight," and a gunner had kept on calling out the calibrated readings "2200...2250...2300...2325," until their voices had taken on the monotonous quality of the fishing boat that puttered somewhere beneath us, The radio in the room behind hummed.

I was waiting impatiently for the fortress guns to open fire at those barges being towed by a tug out at sea, when someone who had been peering through field glasses said the red flag was up on the ship. "Target destroyer moving north represented by floats," the maior (R.T. DuMoulin) called out. "Target destroyer moving north represented by floats," the telephone operator repeated.

Suspense gripped the O-Pip which seemed like the bridge of a ship standing high on the bluff overlooking the sea. The range finders kept on calling out the varying distances of the target.

A soldier moved the hands of a large dial. "That's the telegraph," the colonel (Gordon Y.L. Crossley) whispered in my ear. "It sends back the range to the guns."

"Open 100 right 2," the major called out. "Open 100" meant that the shells were to fall parallel but 100 yards apart, and "right 2" was its location, the colonel explained. The telephone operator leaned forward and called out "Shot 1," We listened intently and heard a soft "plop," and a few seconds later saw a tiny splash beyond the target. "

“Plus 1," the major said, plus meaning that the shell had landed beyond the target. "The two dots (of the target) are a destroyer's length apart," said the colonel, "so that if a shell falls in between we have a direct hit."

"Plus2," the major said, as there was another tiny splash, "Close 100," he ordered, which meant the guns were to fire 100 yards apart but in line. "Plus and minus," he said, as two shells fell on each side of the black dots.

In the colonel's car we drove the quarter of a mile or so from the observation post to the emplacement and arrived just as steel-helmeted crews rushed to man the guns for the second burst of firing.

The order to fire rang out from the high command post, overlooking the guns, and the long grey muzzles swung slowly into range. Straddled on each side of the gun two men peered through the telescopic sights. The sergeant brought his arm down.

There was a short staccato crack and a long hissing whistle, The guns had sub-calibre tubes and were firing one-inch one pound shells instead of the heavy snub-nosed shells that were stored ready for use under the gun platforms. That's why there was no ear-splitting roar, and that's why few people knew there was any firing going on around Vancouver yesterday. lt wasn’t spectacular, but it saved the taxpayers a lot of money.

The muzzles of the guns moved electrically up and down after each salvo. "That's for loading," the sergeant said. "With these B.B. bullets we don't need it; but we're doing it for practice."

The guns are fired by a pistol trigger beside the sights, When a full charge is used recruits usually attach a 30-foot lanyard to the trigger, but experienced artillerymen fire the monster as if they were shooting a .22 (calibre rifle).

Vancouver Defended, Peter N Moogk, pg 95

Vancouver Defended, Peter N Moogk, pg 73

Early in 1940 the Vancouver newspapers ran a series of morale-boosting articles on the airmen and soldiers guarding British Columbia. One month before the fall of France a correspondent was unfortunate enough to describe the Victoria-Esquimalt gun batteries as "miniature Maginot Lines." On February the 14th Peter Stursberg of the Vancouver Daily Province was allowed to observe a firing practice from the flank observation post at Point Grey. Though the Province spoke of "heavy guns...somewhere in Vancouver" being "groomed for business," the facts were more prosaic. Major C.K. Rosebrugh, second-in-command of the 15th Coast Brigade, reported to area headquarters "14th February, A.M. One-inch aiming rifle practice at Point Grey. Visibility was quite poor, especially the left half of the zone where the maximum was about 4,000 yards. A total of 75 rounds of one-inch aiming was (sic) fired in five series at ranges between 2,100 and 2,300 yards. The target consisted of two floats representing a destroyer towed by a launch in the Gulf of Georgia off Point Grey and this practice was, for most of the men. the first time that they had fired the guns to seaward. In addition to the aiming rifles, there were sub-calibre tubes for a 3-pound shell that could also be inserted into the main bore. The tubes permitted live-firing drill at little cost and without wear to the gun's barrel. A 3-pounder shoot occurred on the following day when no reporters were present. For all practice firings maritime traffic was forewarned by the press to stay clear of the target zone and, as an additional warning, a red flag was flown from the battery flagstaff that customarily carried the Union Jack. It was hard to get excited about the firing of a one-inch aiming rifle and Peter Stursberg did his best to dramatize the event.

As the order rang out, the men in the O-Pip (observation post) became tense, Before that we had been chatting and glancing idly out at the two dots moving slowly across the grey sea.

A bombardier, his eye glued to the range finder, had kept on repeating "on sight," and a gunner had kept on calling out the calibrated readings "2200...2250...2300...2325," until their voices had taken on the monotonous quality of the fishing boat that puttered somewhere beneath us, The radio in the room behind hummed.

I was waiting impatiently for the fortress guns to open fire at those barges being towed by a tug out at sea, when someone who had been peering through field glasses said the red flag was up on the ship. "Target destroyer moving north represented by floats," the maior (R.T. DuMoulin) called out. "Target destroyer moving north represented by floats," the telephone operator repeated.

Suspense gripped the O-Pip which seemed like the bridge of a ship standing high on the bluff overlooking the sea. The range finders kept on calling out the varying distances of the target.

A soldier moved the hands of a large dial. "That's the telegraph," the colonel (Gordon Y.L. Crossley) whispered in my ear. "It sends back the range to the guns."

"Open 100 right 2," the major called out. "Open 100" meant that the shells were to fall parallel but 100 yards apart, and "right 2" was its location, the colonel explained. The telephone operator leaned forward and called out "Shot 1," We listened intently and heard a soft "plop," and a few seconds later saw a tiny splash beyond the target. "

“Plus 1," the major said, plus meaning that the shell had landed beyond the target. "The two dots (of the target) are a destroyer's length apart," said the colonel, "so that if a shell falls in between we have a direct hit."

"Plus2," the major said, as there was another tiny splash, "Close 100," he ordered, which meant the guns were to fire 100 yards apart but in line. "Plus and minus," he said, as two shells fell on each side of the black dots.

In the colonel's car we drove the quarter of a mile or so from the observation post to the emplacement and arrived just as steel-helmeted crews rushed to man the guns for the second burst of firing.

The order to fire rang out from the high command post, overlooking the guns, and the long grey muzzles swung slowly into range. Straddled on each side of the gun two men peered through the telescopic sights. The sergeant brought his arm down.

There was a short staccato crack and a long hissing whistle, The guns had sub-calibre tubes and were firing one-inch one pound shells instead of the heavy snub-nosed shells that were stored ready for use under the gun platforms. That's why there was no ear-splitting roar, and that's why few people knew there was any firing going on around Vancouver yesterday. lt wasn’t spectacular, but it saved the taxpayers a lot of money.

The muzzles of the guns moved electrically up and down after each salvo. "That's for loading," the sergeant said. "With these B.B. bullets we don't need it; but we're doing it for practice."

The guns are fired by a pistol trigger beside the sights, When a full charge is used recruits usually attach a 30-foot lanyard to the trigger, but experienced artillerymen fire the monster as if they were shooting a .22 (calibre rifle).

Vancouver Defended, Peter N Moogk, pg 95