Walter Harrington's story

Walter Harrington, who became an officer in the regular army found life as a gunner in the Vancouver defences "deadening." His father's service in the British and Canadian armies impelled him to come north in May 1940 from San Diego, California, to enlist in Canada's armed forces. Harrington's past association with the coast artillery of the American National Guard led him to the Bessborough Armouries. "I went in there," he remembers, "and asked the adjutant about getting into the field artillery. 'Oh yes,' he said, 'join us.' I should have known better. So I went and joined the 15th (Vancouver) Coast Brigade." He was attached to the 58th Heavy Battery and sent to Point Grey in June. The petty vexations that Walter Harrington endured as a gunner still rankle. "At Point Grey they gave me a bedspring with one-by-four boards and two-by-fours for legs and you made a box-like thing out of this and that was a bed. I just hammered the thing together. And we had straw palliasses (mattresses) and no pillow because the army didn't believe in pillows. The guys from here brought pillows from home. The army didn't have any sheets though the air force did."' It might be added that issue blankets were to be marked as government property to discourage theft or sale to civilians, The dress regulations for soldiers on leave struck Harrington as being particularly insensitive. Until the new battledress became available to all ranks in the second half of 1940, recruits were given First World War uniforms consisting of a peaked forage cap, a flared tunic, and riding breeches with cloth puttees. Some of the old outfits disintegrated when they were unpacked. With this order of dress the gunners had to wear a leather bandolier for rifle ammunition. Why a gunner should wear such a thing mystified Harrington. "It had to be polished, but it was completely useless." The ruling of area headquarters on dress was contained in the 15th's Part I Orders for February 1940.

DRESS-SOLDIERS ON PUBLIC STREETS

(a) lt has been observed that soldiers on individual duty or when walking out, are appearing on the streets improperly dressed, i.e., u:ithout greatcoats, or wearing denim trousers or breeches, when their unit is known to be in possession of full supplies of serge clothing or battle dress.

(b) This creates the impression that soldiers are suffering from lack of proper clothing, when, as a matter of fact, the condition is due to the soldiers' negligence to dress properly.

(c) If the order of dress requires the wearing of a greatcoat, a greatcoat will be worn. lf the uniform available to an Infantry unit, under present conditions, is breeches and puttees, a soldier of that unit will not be permitted out of barracks in denim trousers because he finds it less trouble than putting on the breeches and puttees.

(d) Under present conditions, when adequate supplies of new uniforms are not yet available, the above mentioned practice is particularly undesirable. Officers Commanding will, therefore, ensure that all soldiers, when outside of barrack areas, are properly dressed in such uniform as is available to them.

Subsequent orders charged the men with walking about with coats unbuttoned, hands in their pockets, and for "considerable slackness in saluting." For the soldiers the dress problem was not so clear-cut. Walter Harrington received "an old cavalry greatcoat that went down to my ankles which I couldn't wear out (of barracks...). Now to go out on pass, however, they only had so many uniforms so we guys used to trade. You had to go out in battledress so when some fellows came back on pass, then you got a size that was, more or less, your fit and put that on and went out on pass. But you couldn't go out in civilian clothes; you had to go out in uniform. Some guy decided that everyone had to go out in boots and puttees. (...) It was kind of silly because when you were walking around on pass you were clomp, clomp, clomping around in those boots with all those hobnails. This was a problem because you couldn't dance and you couldn't go into somebody's house with your hobnailed boots on - it was crazy. The other thing was that they never provided any transportation so we had to make our own way from the fort down to the streetcar stop at Alma (four miles away)."

DRESS-SOLDIERS ON PUBLIC STREETS

(a) lt has been observed that soldiers on individual duty or when walking out, are appearing on the streets improperly dressed, i.e., u:ithout greatcoats, or wearing denim trousers or breeches, when their unit is known to be in possession of full supplies of serge clothing or battle dress.

(b) This creates the impression that soldiers are suffering from lack of proper clothing, when, as a matter of fact, the condition is due to the soldiers' negligence to dress properly.

(c) If the order of dress requires the wearing of a greatcoat, a greatcoat will be worn. lf the uniform available to an Infantry unit, under present conditions, is breeches and puttees, a soldier of that unit will not be permitted out of barracks in denim trousers because he finds it less trouble than putting on the breeches and puttees.

(d) Under present conditions, when adequate supplies of new uniforms are not yet available, the above mentioned practice is particularly undesirable. Officers Commanding will, therefore, ensure that all soldiers, when outside of barrack areas, are properly dressed in such uniform as is available to them.

Subsequent orders charged the men with walking about with coats unbuttoned, hands in their pockets, and for "considerable slackness in saluting." For the soldiers the dress problem was not so clear-cut. Walter Harrington received "an old cavalry greatcoat that went down to my ankles which I couldn't wear out (of barracks...). Now to go out on pass, however, they only had so many uniforms so we guys used to trade. You had to go out in battledress so when some fellows came back on pass, then you got a size that was, more or less, your fit and put that on and went out on pass. But you couldn't go out in civilian clothes; you had to go out in uniform. Some guy decided that everyone had to go out in boots and puttees. (...) It was kind of silly because when you were walking around on pass you were clomp, clomp, clomping around in those boots with all those hobnails. This was a problem because you couldn't dance and you couldn't go into somebody's house with your hobnailed boots on - it was crazy. The other thing was that they never provided any transportation so we had to make our own way from the fort down to the streetcar stop at Alma (four miles away)."

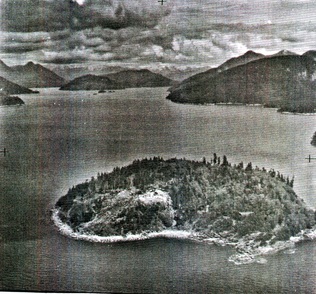

It was policy in the 15th Coast to rotate men within the defensive installations and, like many others, Walter Harrington did a six month stint on Yorke Island. There he experienced more of "what is known as 'chicken shit'." There was no regular leave policy coordinated with the vessels visiting the island. "From Vancouver there were boats going by, but not only that, there was a regular passenger boat calling in there once a week, then a water boat and a supply boat coming in (from Kelsey Bay where other steamships stopped), one on a Tuesday and one on Friday. It was absolutely ridiculous to not give people passes when you were that close to home, - something like eighty percent of the men came out from Vancouver, married men, men with families - absolutely none of them could go. They were afraid they might not get back in time and (. . . ) we had to be in the front line. Most of those who had volunteered for service with the regular army had done so with the hope of going overseas and seeing some action. Harrington was no exception; he was marking time in the coastal defences. "The thing that kept us going," he says, "was the prospect of getting out of Canada. (...) A very good friend of mine went down to Arnprior - his home - and a friend of his mother was raising the 24th Anti-Tank Battery out of Toronto. And so he went up to Camp Petawawa and saw him and got a draft for himself and he asked that I be requested. So I got requested to join the 24th Anti-Tank Battery; that's how I got out. I went overseas in October 1941, which is what I had joined to do." He remembers four others who came up from the United States and joined the 15th Coast. Three stayed for only two or three weeks; "they couldn't hack it and they deserted."

Vancouver Defended, Peter N Moogk, pg 101

Vancouver Defended, Peter N Moogk, pg 101