Narrows North

Fort Record Book

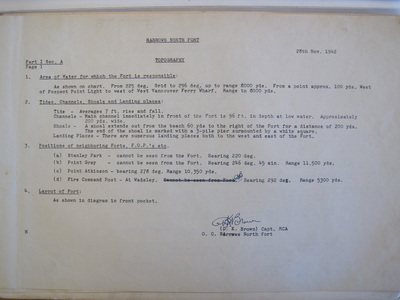

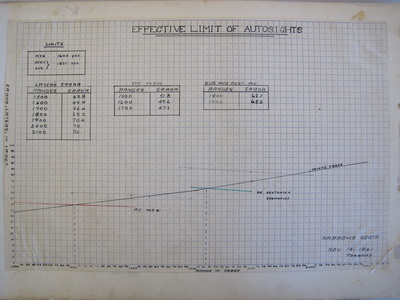

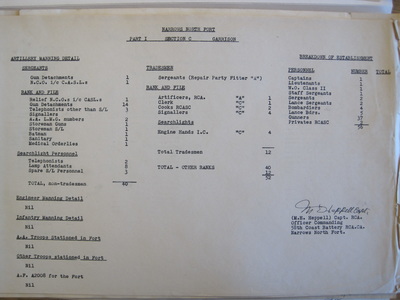

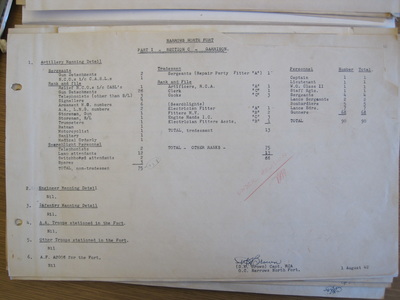

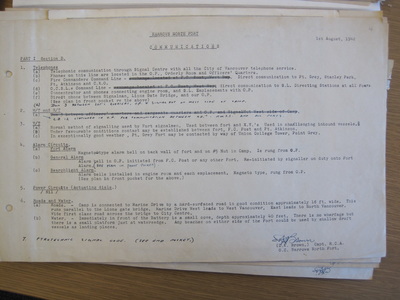

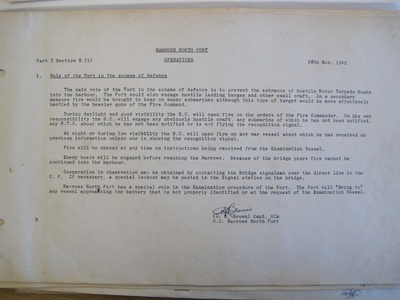

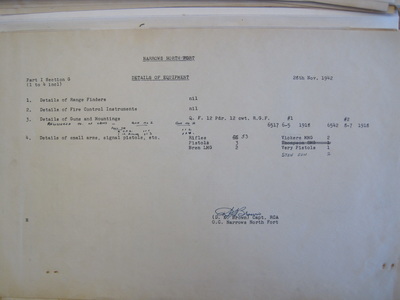

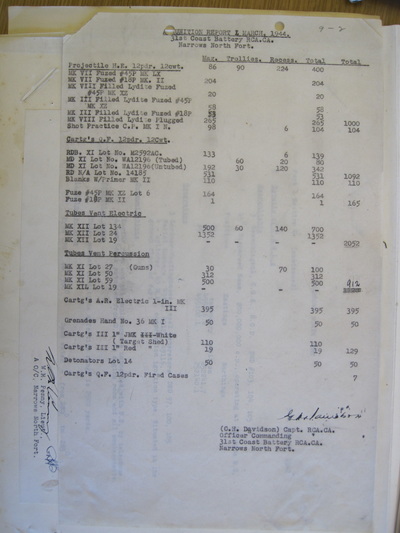

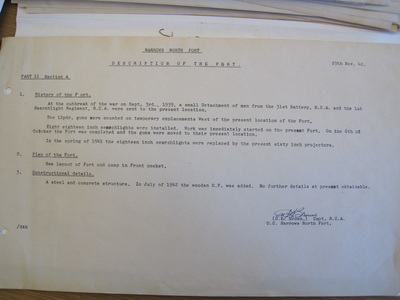

The Fort Record Book contained the technical information for the fort. Armament, personnel and equipment are listed.

The Fort Record Book contained the technical information for the fort. Armament, personnel and equipment are listed.

The Liberty Ship Incident

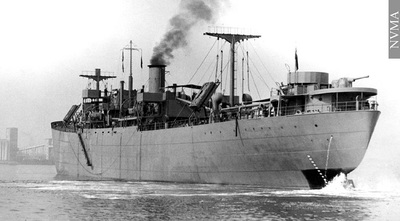

The incident that … causes embarrassed laughter among veterans of the 15th Coast occurred on September 13th, 1942. This was when the gunners proved that they could sink a ship, albeit a friendly one.

D. Ken Brown had taken over command of the Narrows North detachment in late June 1942 and he believed in a firm application of the port security regulations. With the approval of Col. Hood, the guns came into action. The firing of heave-to rounds provided useful training for the troops and it cowed the fishermen into conforming with the wartime rules. "Once heaving tasted the idea of using the rules to provide practice," recalls Ken Brown, "then, on the slightest opportunity, when it was permissible for us to fire, even though we suspected rather strongly that they were friendly, (...) we fired that round, as the rules called for it, two degrees ahead of the target so that the splash could be seen. It was more realistic than the normal gun drill." This gave young Lieut. Brown a reputation: "the nickname I acquired, 'Gunfire Brown,' was because during the first month that I was in command I remember firing something like thirty-one rounds."

Ken Brown remembered that on that fateful Sunday afternoon, when "the famous or infamous misadventure" happened, it was overcast and windy. A fish-packer chugged in past Point Atkinson and ignored all the signals to identify himself . As the boat approached the narrows, the fort there received an order to fire a stopping round. "The message came from the examination vessel stationed just off Point Atkinson." states Ken, "I think it was a radio message. The battery was at rest normally until an alarm was sounded and that was activated by messages received from the examination vessel. We were away from the gantry and had to run several yards gathering our helmets and equipment. We arrived on the scene rather disturbed." When the gun was fired "we had the desired result: the fish boat stopped." The plugged shell, however, had not stopped. Instead of kicking up a splash and sinking, the round hit a wave and ricocheted across the water at an oblique angle. In its path lay a freighter recently launched by Burrard Dry Docks and now undergoing speed trials over a measured mile in English Bay. This was the 9,600 ton Fort Rae. E.L. "Paddy" Copeland, who was on the beach at Ambleside with his wife, saw what was happening despite the haze on the water. "When we saw this shot go skipping across the water, I said to my wife 'it's going to hit that freighter' (... ) they hit it amidships right at the waterline (...) it went right through it. That's the one and only time I saw that happen." The damage was greater than anyone imagined. The non-explosive shell had entered the No. 3 hold, just forward of the engine room, and left a neat hole above the waterline on the near side of the Fort Rae. Yet unseen by those present, the shell tumbled after impact and, striking sideways, it punched out a larger hole on the far side of the hull below the waterline. Ken Brown picks up the story: "there was no alarm until they finished that testing run and turned to come into the (inner) harbour, at which time the hold was flooding and there was obviously panic. They beached the hull just inside the Lions' Gate Bridge (...) I wasn't very popular with the ship's captain and Col. Hood wasn't very pleased with the incident."

The beached ship was subsequently patched up and floated off the north shore tidal flats to be returned to the builder's yard. An army court of inquiry was set up [o investigate the episode and the charges of Captain Semple and his crew that the gunners had deliberately fired three shells at their ship, including a shot through the rigging. "Fortunately for me," remarks Ken Brown, "we were able to prove that we had only fired one round legally and within the rules." A.F. Menzies, retired chief engineer of the Burrard DryDocks, remembers a distressed gunner from the fort saying "For God's sake, don't talk about it; there's been enough misery." The archivist of the shipyard, J.R. Holden, describes the accident as "quite a joke - it was supposed to be a military secret."

Vancouver Defended, Peter Moogk, Pg 100

The incident that … causes embarrassed laughter among veterans of the 15th Coast occurred on September 13th, 1942. This was when the gunners proved that they could sink a ship, albeit a friendly one.

D. Ken Brown had taken over command of the Narrows North detachment in late June 1942 and he believed in a firm application of the port security regulations. With the approval of Col. Hood, the guns came into action. The firing of heave-to rounds provided useful training for the troops and it cowed the fishermen into conforming with the wartime rules. "Once heaving tasted the idea of using the rules to provide practice," recalls Ken Brown, "then, on the slightest opportunity, when it was permissible for us to fire, even though we suspected rather strongly that they were friendly, (...) we fired that round, as the rules called for it, two degrees ahead of the target so that the splash could be seen. It was more realistic than the normal gun drill." This gave young Lieut. Brown a reputation: "the nickname I acquired, 'Gunfire Brown,' was because during the first month that I was in command I remember firing something like thirty-one rounds."

Ken Brown remembered that on that fateful Sunday afternoon, when "the famous or infamous misadventure" happened, it was overcast and windy. A fish-packer chugged in past Point Atkinson and ignored all the signals to identify himself . As the boat approached the narrows, the fort there received an order to fire a stopping round. "The message came from the examination vessel stationed just off Point Atkinson." states Ken, "I think it was a radio message. The battery was at rest normally until an alarm was sounded and that was activated by messages received from the examination vessel. We were away from the gantry and had to run several yards gathering our helmets and equipment. We arrived on the scene rather disturbed." When the gun was fired "we had the desired result: the fish boat stopped." The plugged shell, however, had not stopped. Instead of kicking up a splash and sinking, the round hit a wave and ricocheted across the water at an oblique angle. In its path lay a freighter recently launched by Burrard Dry Docks and now undergoing speed trials over a measured mile in English Bay. This was the 9,600 ton Fort Rae. E.L. "Paddy" Copeland, who was on the beach at Ambleside with his wife, saw what was happening despite the haze on the water. "When we saw this shot go skipping across the water, I said to my wife 'it's going to hit that freighter' (... ) they hit it amidships right at the waterline (...) it went right through it. That's the one and only time I saw that happen." The damage was greater than anyone imagined. The non-explosive shell had entered the No. 3 hold, just forward of the engine room, and left a neat hole above the waterline on the near side of the Fort Rae. Yet unseen by those present, the shell tumbled after impact and, striking sideways, it punched out a larger hole on the far side of the hull below the waterline. Ken Brown picks up the story: "there was no alarm until they finished that testing run and turned to come into the (inner) harbour, at which time the hold was flooding and there was obviously panic. They beached the hull just inside the Lions' Gate Bridge (...) I wasn't very popular with the ship's captain and Col. Hood wasn't very pleased with the incident."

The beached ship was subsequently patched up and floated off the north shore tidal flats to be returned to the builder's yard. An army court of inquiry was set up [o investigate the episode and the charges of Captain Semple and his crew that the gunners had deliberately fired three shells at their ship, including a shot through the rigging. "Fortunately for me," remarks Ken Brown, "we were able to prove that we had only fired one round legally and within the rules." A.F. Menzies, retired chief engineer of the Burrard DryDocks, remembers a distressed gunner from the fort saying "For God's sake, don't talk about it; there's been enough misery." The archivist of the shipyard, J.R. Holden, describes the accident as "quite a joke - it was supposed to be a military secret."

Vancouver Defended, Peter Moogk, Pg 100